Between 1918 and 1923, following World War I, the Kuvayı Milliye (National Forces) Movement succeeded in spreading the struggle for independence not only within its own territories but across the entire Islamic world, despite the occupation of Ottoman lands and the immense suffering of its people. The Kuvayı Milliye became a symbol of resistance that resonated not only among the Turkish, Kurdish, and Arab nations but also in the collective conscience of the ummah (Islamic community).

The Liberation of a Nation, the Hope of the Ummah: The War of Independence and the Kuvayı Milliye Movement

After the Tripolitanian, Yemeni, and Balkan Wars, the flames of World War I engulfed the Ottoman geography. From Çanakkale to Selman-ı Pak, from Kutü’l-Amare to the Caucasus, from Sinai to Palestine and Syria, the Ottoman armies fought arduous battles on numerous fronts. The cost of these wars was heavy: one million soldiers from the Ottoman army were martyred, and hundreds of thousands were captured or went missing.

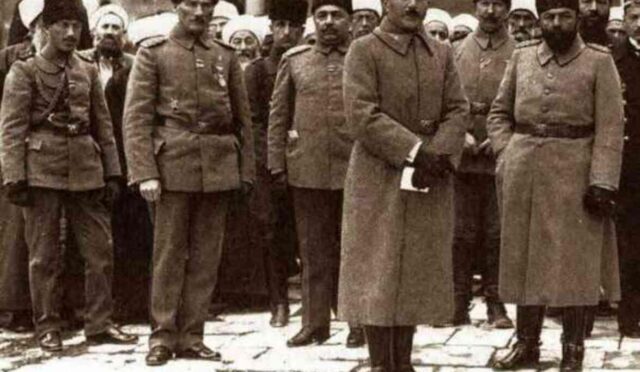

Turkish, Kurdish, Arab, and even Christian Ottoman citizens fought shoulder to shoulder on these challenging fronts. When you visit Ottoman cemeteries from Çanakkale to Libya, from the Balkans to Yemen, and from the Caucasus to Iraq, you see the martyrs of these nations lying side by side, united in destiny.

Between 1910 and 1918, nearly every family in Ottoman lands lost a martyr. Homes were left with only children, women, and the elderly; the lands were filled with orphaned children and widowed women. The entire geography was also suffering from poverty. The Ottoman lands, echoing with deep sorrow and lamentations, became silent witnesses to pain.

In 1918, immediately after World War I, Istanbul was occupied. Then, Izmir, Thrace, and all corners of Anatolia fell under the occupation of British, French, Greek, and Italian forces. The capital, Istanbul, was under siege; the Caliph was virtually imprisoned in his palace. However, the commanders and soldiers of the Ottoman army, who had previously resisted invaders in Tripoli and Algeria, were now preparing to demonstrate the same resistance on Anatolian soil.

Sultan Vahdettin secretly supported his commanders in establishing units in their regions and initiating resistance against the occupiers, providing both material and moral aid. This resistance would resemble the struggles of heroes like Emir Abdülkadir of Algeria, Abdülhamid bin Badis, Abdülkerim el-Hattabi, Omar Mukhtar, and the Caucasian Eagle, Sheikh Shamil. Our renowned poet and writer Süleyman Nazif, in his writings, often cited the lives of these heroes as examples in the struggle against imperialism.

Across a vast geography stretching from Edirne to Kars, from Izmir to Maraş, and from Rize to Diyarbakır, the people, exhausted from years of war, rose one last time. The news of the occupation of Istanbul, the center of the Caliphate, and Anatolia plunged the Islamic world into deep sorrow. From Bengal to South Africa, from Indonesia to Tunisia, and from India to all corners of Africa, Muslims mobilized for the liberation of these lands, which were the heart of the Islamic world. Every corner stood up to provide material and moral support to the Kuvayı Milliye movement initiated by Ottoman commanders. This resistance would become not just the epic of one nation’s liberation but a saga that echoed in the conscience of the entire ummah.

In 1919, the Indian Khilafat Movement, established in India, launched campaigns across a vast region encompassing present-day Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, and Kashmir, collecting financial aid for the Kuvayı Milliye Movement. Led by the Ali brothers, Şevket Ali and Muhammed Ali Cevher, prominent Muslim thinkers of the time, such as Abul Kalam Azad, Abul Ala Maududi, and Allama Muhammad Iqbal, traveled across the Indian subcontinent, delivering passionate speeches and writing supportive articles in newspapers and magazines.

A small pamphlet written by Abul Ala Maududi on the occupation of Izmir and the atrocities committed was photocopied and circulated hand to hand, mobilizing the people. However, this support was not limited to India. From the Malay Peninsula to the Arab world, and from all corners of Africa, Muslim scholars and people took to the streets despite the pressures of occupying forces, delivering sermons and organizing aid campaigns for the Ottomans.

Between 1921 and 1923, the amount of aid sent from India to Turkey alone reached 122,000 British pounds, equivalent to approximately 782,070 Turkish liras at the time. A significant portion of these funds was deposited into an account opened in Mustafa Kemal Pasha’s name at the Ottoman Bank’s Ankara branch. The Indian Khilafat Movement was not just an aid initiative but also a manifestation of the ummah’s heartfelt bond and spirit of solidarity with the Ottomans (Turkey).

The primary goal of the Defense of Rights Societies established in almost every city in Turkey was first to liberate Thrace, Istanbul, and Anatolian lands from imperialist occupiers and then to free all oppressed Muslim geographies from colonial yokes. The spirit of this blessed struggle, the Kuvayı Milliye, spread like waves from Edirne to Maraş, from Kastamonu to Damascus and Palestine.

Brave hearts gathered in every corner, transforming whatever materials they could find into weapons. They turned stove pipes into cannons, wood into swords, and ropes into stirrups, heroically fighting against imperialist forces despite scarce resources. The inspiration for this sacrifice and resistance lay in the seeds sown on the Çanakkale front. The spirit of Kuvayı Milliye, which sprouted in Çanakkale, transformed into courage and revival across Anatolia, resonating in the hearts of the people. This spirit was not just the name of a resistance but the heart of a great epic of a nation’s struggle for independence.

The first spark of the War of Independence was ignited on December 19, 1918, with a bullet fired at French soldiers in the village of Karakese, Dörtyol. Those who had planned to partition Ottoman lands through the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement and the 1917 Balfour Declaration never anticipated that a nation, defeated and exhausted from long wars, would display such determined resistance. However, Anatolia witnessed a total resistance, supported not only by its own children but also by Muslim youth and scholars from all corners of the ummah.

From Libya, Sheikh Senusi; from Iraq, Uceymi Pasha and his tribe; from Syria and Palestine, Izzettin el-Kassam; from the Indian subcontinent, Abdurrahman Riyaz; from Egypt, Muhammad Salih Harp Pasha; and many other heroes flocked to Anatolia to support the Kuvayı Milliye epic. Muhammad Salih Harp Pasha, who had participated in the Tripolitanian War, recorded important details about the Sakarya and Izmir battles in his memoirs. Meanwhile, in the ranks of Şefik Özdemir Bey, an Egyptian graduate of Al-Azhar University who fought against the British around Mosul, Kirkuk, and Sulaymaniyah, were young men from Algeria, Morocco, Mauritania, Libya, and Tunisia.

Anatolia became a battlefield not only for swords but also for pens and sermons. From Sheikh Senusi to Emir Shakib Arslan, from Mehmet Akif Ersoy to Bediüzzaman Said Nursi, many Muslim scholars and thinkers delivered sermons from Anatolia to Aleppo, from Mosul to Kirkuk, winning the hearts of the people for the resistance. Particularly, Mehmet Akif Ersoy, welcomed in Ankara as the “Poet of Islam,” took on the spiritual leadership of the National Struggle through his speeches across Anatolia, starting from the pulpit of Nasrullah Mosque in Kastamonu.

The support of Islamic scholars was significant during the Erzurum and Sivas Congresses. Even before the Sivas Congress, a conference titled “Islamic Unity,” organized by Mehmed Akif, Bediüzzaman Said Nursi, and Sheikh Senusi, was held with the participation of dozens of scholars from different parts of the Islamic world. The joint declaration issued at this conference proclaimed that supporting the War of Independence was a shared duty (farz al-ayn) for all Muslims. Thus, Anatolia’s resistance became the collective conscience of not just one nation but the entire ummah.

The leadership of the National Struggle was shaped by the joint will of Ottoman army commanders and Muslim scholars. Mustafa Kemal Pasha, who began publishing the “Minber Newspaper” in 1918 to call the Muslim world to jihad against imperialists, was chosen as the leader of the Defense of Rights and National Struggle Movement. This call resonated across the Islamic world. Through his speeches and writings, Mustafa Kemal Pasha called Muslim peoples to a united struggle against imperialism. His leadership became a symbol of both Anatolia’s resistance and the ummah’s desire for independence.

From Bangladesh’s national poet Kazi Nazrul Islam to Egypt’s poet Ahmed Shawqi, from Pakistan’s national poet Muhammad Iqbal to Iraq’s poet Maruf al-Rusafi, hundreds of Muslim poets and scholars wrote poems and articles about Mustafa Kemal Pasha. In these works, Mustafa Kemal Pasha was likened to great Islamic commanders like Khalid ibn al-Walid and Saladin. While Muslim peoples called him “Asad al-Islam” (Lion of Islam), the Mufti of Damascus bestowed upon him the title “Sayf al-Islam” (Sword of Islam) after the defeat of the Greek army in the Great Offensive.

To make the voice of the National Struggle heard worldwide, the Anatolian Agency was established under the leadership of Halide Edip. One of the agency’s first correspondents was Abdurrahman Peşaveri, a devoted warrior of the National Struggle from Afghanistan. His efforts carried the spirit of resistance to the entire Islamic world.

After the Great Victory, jubilant celebrations were held in Muslim lands from India to Morocco. In Tunisia, the people of the Maghreb adorned the streets with flags in honor of the victory; mosques and masjids were illuminated with lanterns at night. In Jerusalem, Palestinians offered prayers of gratitude for this blessed victory. The victory was celebrated with Mawlid recitations, Quranic tilawat, salawat, and takbirs rising to the skies. Prayers were dedicated to the heroic army of the National Struggle and the honor of Islam. For this victory was not just Anatolia’s but a liberation epic resonating in the hearts of every member of the ummah.

The opening of the Grand National Assembly in Ankara on April 23, 1920, took place in a deeply spiritual atmosphere. After the Friday prayer at Hacı Bayram Mosque, the sacred banner, the Quran, and the Blessed Beard of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) were carried in procession to the Assembly building. This blessed march symbolized the spirit and spiritual foundation of the National Struggle.

Behind the Assembly podium, a plaque inspired by the Quranic verse from Surah Ash-Shura (42:38), “They conduct their affairs by mutual consultation,” was hung. The banner was erected on the podium, and the Quran and the Blessed Beard were placed upon it. The opening was crowned with prayers, and sacrifices were made outside to celebrate this historic day. A room in the Assembly building was designated as a mosque, and Muezzin Hüseyin Efendi called the deputies to prayer by reciting the adhan during Assembly sessions.

This historic opening was not just the inauguration of an Assembly but also an expression of the nation’s commitment to the struggle for independence. Libyan scholar Sheikh Senusi, who invited the people and scholars to the spirit of Kuvayı Milliye, called the National Struggle the “Great Jihad,” while Mustafa Kemal Pasha described the Grand National Assembly government established on May 3 as “the only hope of Islam.” These words revealed that the National Struggle and the Grand National Assembly were not just the hope of one nation but of the entire Islamic world.

In his speeches to press representatives in Izmit on January 16 and at Zağanos Pasha Mosque in Balıkesir on February 7, Mustafa Kemal Pasha expressed the spirit of the National Struggle and the fundamental principles of the Grand National Assembly with these words:

“The government of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey has been established in accordance with the noble principles of Sharia, based on consultation, justice, and obedience to divine command. The issue of the Caliphate is not a direct necessity for the Turkish state. However, when considering the Islamic world, the meaning and existence of the Caliphate may come into question. For the Caliphate does not belong solely to the Turks; it belongs to the exalted Islamic world. Today, since the Islamic world is under occupation, the Grand National Assembly will preserve the Caliphate as a point of hope until a level is reached where the issue of the Caliphate can be resolved.”

These statements emphasized the spiritual and moral values on which the Assembly was founded and highlighted the Caliphate as a unifying hope for the Islamic world. At the same time, they underscored that the National Struggle was not just a nation’s fight for independence but a step toward the revival of the entire Islamic world.

Since then, Afghanistan, one of the world’s most oppressed peoples, has gone down in history as the first country to recognize the Grand National Assembly. For this reason, Afghanistan holds a special place in the hearts of the Turkish people since the War of Independence. With the agreement signed in Moscow on March 1, 1921, Afghanistan became the first country to officially recognize the Anatolian government and the first state to send a diplomatic representative to Ankara. At that time, both Turkey and Afghanistan were engaged in a relentless struggle against British imperialism. Hence, the friendship and solidarity between them carried profound meaning.

On March 12, the Grand National Assembly of Turkey adopted Mehmed Akif’s “İstiklâl Marşı” (Independence March) as the “National Anthem” with an “overwhelming majority,” with only one member opposing. After its adoption, the poem was requested to be read once more. Hamdullah Suphi then took the podium and recited the İstiklâl Marşı with great enthusiasm. Mustafa Kemal Pasha and the deputies listened to the national anthem standing, greeting it with great respect.

In a letter to the President of the Indian Khilafat Committee on February 9, 1923, Mustafa Kemal Pasha expressed these meaningful words:

“The outcome of our great victory will not only affect the destiny of Turkey but will also encourage all oppressed nations to take action against the oppressors who hold their lives and independence under pressure.”

In conclusion, between 1918 and 1923, following World War I, the Kuvayı Milliye Movement succeeded in spreading the struggle for independence not only within its own territories but across the entire Islamic world, despite the occupation of Ottoman lands and the immense suffering of its people. The Kuvayı Milliye became a symbol of resistance that resonated not only among the Turkish, Kurdish, and Arab nations but also in the collective conscience of the ummah. From India to Tunisia, from Indonesia to Egypt, Muslim peoples united to provide material and moral support to the Ottomans, strengthening the spirit of the National Struggle. The War of Independence was not just a nation’s fight for freedom but a shared struggle to break the chains of oppression for all oppressed geographies. Under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Pasha, the inspiration of this struggle transformed into both the freedom of the Turkish nation and the revival of the Islamic world. This victory not only liberated Turkey but also encouraged oppressed nations worldwide. The National Struggle proved that a nation’s determination for independence could also become a source of resistance and hope for all humanity.

January 8, 2025

Turan Kışlakçı : https://kritikbakis.com/islam-dunyasinin-ilk-buyuk-direnisi-istiklal-harbi-ve-kuvayi-milliye/